At cell division, or mitosis, the nucleus of the cell divides. Each chromosome within the nucleus is first duplicated, and one copy passes to each daughter nucleus, and hence to each daughter cell.

Read Morebiology

morphic fields

A field is a region of physical influence. Fields are not a form of matter, rather, matter is energy bound within fields. In current physics, several kinds of fundamental fields are recognized: the gravitational and electro-magnetic fields and the matter fields of quantum physics.

The field concept in biology has its origin in the work of Hans Driesch, although the concept itself was elaborated by A. Gurwitsch and P. Weiss. (see account in Gerry Webster and Brian Goodwin, Form and Transformation, pp 94-100) For Joseph Needham, fields are "wholes actively organizing themselves."

In the last decade of the nineteenth century, the embryologist Wilhelm Roux proposed a "developmental mechanics" (Entwicklungsmechanik ) to account for origin and maintenance of organisms through a causal morphology that would reduce them to a "movement of parts," and would prove that biology and physics were completely one with each other. Roux sought to transform biology from a purely historical into a causal discipline through analytic thought and experiment. His "mosaic theory" described development as the self-differentiation of hereditary potentialities with the irreversible functional differentiation among cells. This hypothesis was supported in part by Roux's own experiments at the marine biological station in Naples. When he killed one of the first two cleavage cells in a frog's egg, the surviving cell, as he expected, gave rise to only half of a normal embryo.

in 1891, while working at the Naples station with a different organism, Hans Driesch obtained radically different results. Driesch demonstrated that, contrary to the Roux-Weismann hypothesis, each cell of a sea urchin embryo, when isolated at the two-cell stage, does not produce a half-embryo but a complete, miniature pluteus larva of normal form. (see mechanism / vitalism for philosophical interpretations of these experiments.)

Read MoreMorphogenesis

Morphogenesis is the process by which the phenotype develops in time under the direction of the genotype.

The explanation of morphogenesis requires a theory of the gene as well as theories for those properties of the organism revealed by experimental embryology and experimental morphology.

morphology

Morphology is an "account of form," an account that allows us a rational grasp of the morphe by making internal and external relations intelligible. It seeks to be a general theory of the formative powers of organic structure. The Pre-Darwinian project of rational morphology was to discover the "laws of form," some inherent necessity in the laws which governed morphological process. It sought to construct what was typical in the varieties of form into a system which should not be merely historically determined, but which should be intelligible from a higher and more rational standpoint. (Hans Driesch, 1914, p. 149)

Read Morenatural form

"Organic forms have a general character which distinguishes them from artificial ones.... We come then to conceive of organic form as something which is produced by the interaction of numerous forces which are balanced against one another in a near-equilibrium that has the character not of a precisely definable pattern but rather of a slightly fluid one, a rhythm...There is, in a human work of sculpture, no actual multitude of internal growth-forces which are balanced so as to issue in a near-equilibrium of a rhythmic character. We should therefore not expect that works of art will often arrive at the same type of form as we commonly find in the structures of living matter. Much more can we anticipate an influence of man's intellectualizing, pattern-making habit of simplification, diluted perhaps by an intrusion of unresolved detail." (Waddington (1951) in L.L. Whyte, ed. Aspects of Form)

Read Morenatural selection

In his book On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection (1859) Darwin argued because "variations useful in some way to each being in the great and complex battle for life" do occur sometimes in thousands of generations in the wild, and because "many more individuals are born than can possible survive," then we cannot doubt that "individuals having any advantage, however slight, over others would have the best chance of surviving and of procreating their kind," while "any variations in the least degree injurious would be rigidly destroyed." It is, then, the "preservation of favourable variations and the rejection of injurious variations" that "I call Natural Selection." (from: M.J.S. Hodge, "Natural Selection: Historical Perspectives" in Keywords in Evolutionary Biology, p.212)

Read Moreneoteny

Neoteny: the neural development that certain species, notably humans, continue to experience after birth. Man is born immature and helpless. He is not capable of locomotion or of any of the directed, volitional behavior indispensable for self-preservation. The survival of the neonate is predicated on devoted parental care.

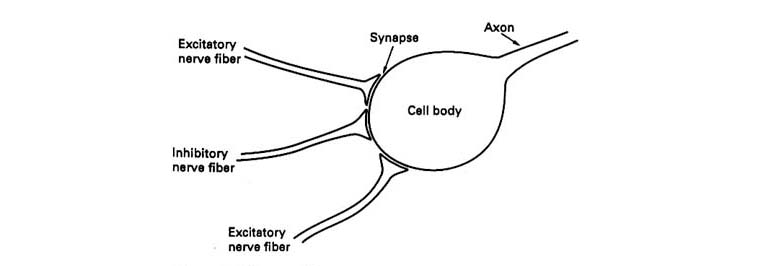

Read Moreneuron

Neurons are rather different from most cells. Mature neurons do not move about, nor do they divide. If a mature neuron dies, it is rarely replaced by a new one. Neurons have a more spikey shape than most cells, and the axon of a neuron can be very long -- as much as several feet. Neuroscientists today believe that the brain records an event by strengthening the connections between groups of neurons that participate in encoding the experience. (see engram)

Read Moreorganism

"Organism" is derived from the same word as organ: in Latin, organum ; in Greek, organon, which means tool, and was the title given to Aristotle's logical writings to emphasize the idea of logic as a tool helping the other sciences. The instrumental view lies to some degree within the word organism itself: a system of organs, a whole composed of parts, where each part is a functional tool related to the other parts and the whole.

Read Morephantom limbs

The eminent Philadelphia physician Silas Weir Mitchell first coined the phrase "phantom limb" after the Civil War. In those preantibiotic days, gangrene was a common result of injuries, and surgeons sawed infected limbs off thousands of wounded soldiers. After amputation of movable, functional extremities, the phantom limb seems to be experienced in close to 100 per cent of cases. Oliver Sachs describes them as "fossil images" but explains them as the persistence of pathological excitation to the peripheral nerves, especially if there is formation of a neuroma in the stump. (see A Leg to Stand On, p.194,n.) (V. S. Ramachandran has convincingly shown that the locus of the phantom limb is in the brain, not near the hand or leg.

Read Morephyllotaxis

Phyllotaxis (gr: phyllous means leaf, taxis means order) refers to the arrangement of leaves on a stem or florets in a composite flower such as a sunflower or pinecone along logarithmic spirals, or summation series, in which each term is the sum of the two preceding ones: 1,2,3,5,8,13,21,34,55,89,144 etc.. The scales form in double spirals which radiate from the center, one clockwise, the other counterclockwise. The surprising feature is that the number of spirals in one direction is related to the number in the other direction as two adjacent numbers in the Fibonacci series.

Read Morepopulation/typological

One of the changes in biological thinking brought on by Darwinism is the replacement of the typological thought of the morphological rationnalists by the "population thinking" of the current neo-Darwinist synthesis.

Traditional Biology seeks to be a science of forms. The Linnean hierarchy, which is more empirical that rational, seeks to classify forms through a structure of nested classes (taxa) of the traditional, Aristotelian kind, whose members are individual organisms. In this system, a "higher" taxon can be said to be more 'abstract' in relation to a lower one, requiring fewer properties for membership and with a greater extension. But according to Driesch, the Linnean hierachies of genera and species were only related on the basis of empirical abstraction, not on the kind of fundamental concepts that carry principles of division and allow for a rational systematics. In the latter case, according to Driesch, "The so-called ' genus' ... then embraces all its 'species' in such a manner that all peculiarities of the species are represented already in properties of the genus." (The Science and Philosophy of the Organism, p.245)

positional info

One way of explaining regulation is to think of cells being able to obtain positional information as to where they are and to use that information in development. This way, cells can be moved about and interchanged (in experiments or accidents) without disturbing the developmental process. Gradient fields could be one source of positional information. (see also morphic fields) For Lewis Wolpert, "positional information is about graded properties" measured with reference to a "coordinate system." Wolpert's simple "French flag" model appealed to the "non-mathematical but theoretically minded." A gradient described as a straight inclined line, could have threshold points translating into patterns (eg red, white, and blue). But "just what moves this answer beyond the realm of tautology remains obscure." Evelyn Fox Keller

Read MoreProprioceptive: sense

The proprioceptive sense informs us about the position of our own limbs in relation to one another and to the space around us. Its sensations come from the muscles and tendons and are not localized. The proprioceptive and tactile sensations combine to constitute the haptic. Proprioceptive feedback is an important developmental component in the sense of agency.

reentry

For Gerald Edelman, reentry is the unique feature of higher brains. It is an ongoing recursive, and massively parallel process of signalling back and forth along reciprocal connections in the brain which integrates the various functionally segregated properties of brain areas despite the lack of a central coordinative area. One striking consequence of reentry is the widespread synchronization of activity of different groups of active neurons. Edelman compares the interconnections of functional clusters in the brain to a network of coupled springs, which propagate any perturbation throughout the system. This is the essential contemporary image: the rhizome, the network -- Empire.

Read Morereplication

Charles Darwin showed how "organs of extreme perfection and complication, which justly excite our admiration" arise not from God's foresight by from the evolution of replicators over immense spans of time. Freeman Dyson reminds us that life consists of both metabolism and replication, and that the two may have started separately. (In its pure state, replication can only be parasitic.) He subscribes to Lynn Margulis' theory that RNA is the oldest and most incurable of our parasitic diseases. (see prokaryote / eukaryote) Genetics is concerned with the replication and variation of of genes in a population (and their impact on adaptation. (See genotype / phenotype )

John von Neumann proved that a machine could be designed that could replicate itself. The logical problem is how to avoid infinite regress that would require the instructions: "how to build machine (how to build machine (how to build machine (etc.)))" If the instructions merely stated "how to build the machine" it would work once and then stop. The new machine would be unable to replicate itself.

The self-replicating machine requires a certain threshold of complexity with a controller that is able to use the same instructions for its own operation as well as for replication. Thinking of the instructions as a "blueprint" the machine is both able to carry out the instructions and copy them as separate operations.

Read MoreRhizome

The Rhizome is one of a panoply of concepts that Deleuze and Guattari deploy in A Thousand Plateaus to describe the dynamics of their nomadology. While they reject binarism, which they consider to be founded on the transcendence of the one, many of Deleuze and Guattari's concepts are detailed "in contrast to".

Read Moresymbiosis

The term symbiosis was defined by the German mycologist Anton De Bary (1879) as meaning the "living together" of "dissimilar" or "differently named" organisms.

Today, in most current biological literature, it is taken to mean "mutualistic biotrophic associations" (biotrophy: one partner requires a nutrient that is a metabolic product of the other partner.) For example, lichens consist of algal and fungal components in nearly equal mass in symbiosis.

T-cells, B-cells

B-cells are formed in the bone marrow, and provide humoral immunity mediated by antibodies. They can recognise parts of antigens free in solution, by fitting them to the antibodies they carry on their surface. When a particular B-cell come into contact with an antigen which it fits, the B-cell swells and divides (through mitosis, or clonal selection)and the new activated B-cells (Plasma cells) secrete antibodies proteins that attack the invader. Once activated, a B-cell can pump out more than 10 million antibody molecules per hour. The antibodies neutralize or precipitate the destruction of the antigens by complement enzymes or scavenger cells. The B-cell can also produce different isotypes of the antibodies, who fit the same antigen but who defend the body in different ways.

Read Moreteleology

In the Timaeus, Plato pictured the natural world as the product of a divine craftsman who looked to the world of eternal being for his model of the good and then created a natural order that was as good as it possibly could be. ("Teleology", by James C. Lennox, in Keller and Lloyd, eds. Keywords in Evolutionary Biology ) This model is the origin of what is sometimes referred to as "external teleology." The "externality" is twofold: the agent whose goal is being acheived is external to the object, and the value is the agent's value, not the object's. (This is much closer to the idea of the machine)

Read More