The Judeao-Christian account of creation is an account of the origin of form, not of matter. "In the beginning..the earth was without form, and void."... The passage deals at length with the origin of order.

For Aristotle, the generation of each organism was the result of a male formal cause (conveyed by the semen) and a female material cause (the menstrual blood.)(see epigenesis) cf body / soul.

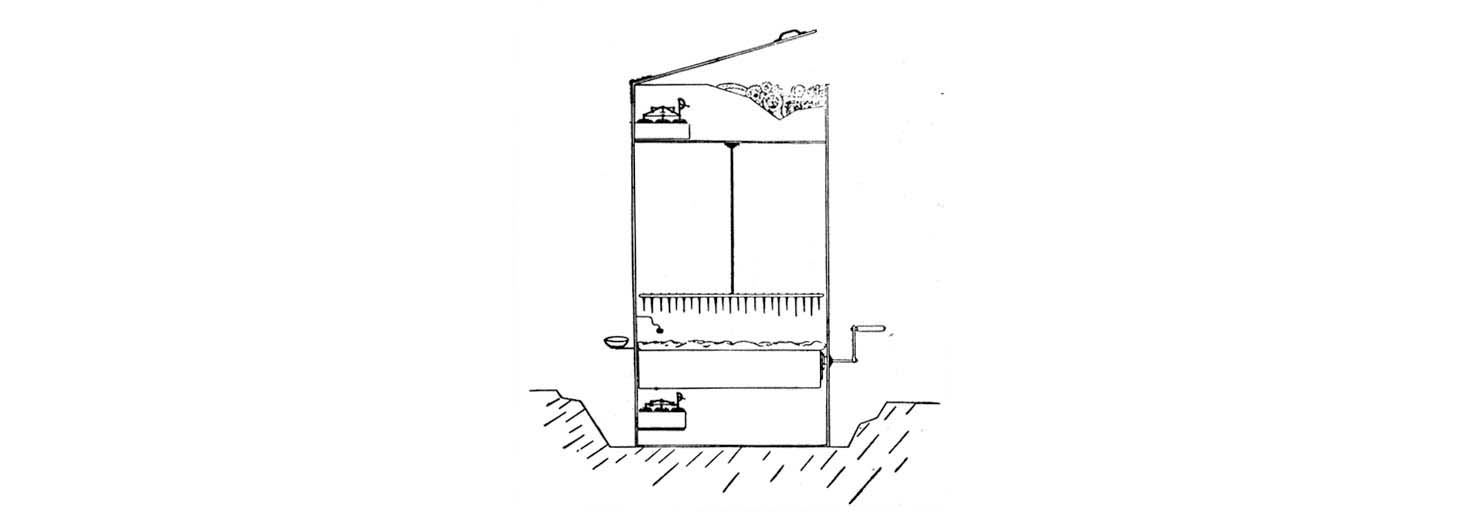

The "hylomorphic" model separates a form that organizes matter and a matter prepared for the form. Gilbert Simondon bases his critique of the hylomorphic model on "the existence, between form and matter, of a zone of medium and intermediary dimension."

A formalist concept presupposes a contrast between form and matter. Indeed, without this distinction the absolutization of form makes no sense. "When we look upon the work of art, the means and the materials are forgotten and it is satisfying in itself as form." (Gottfried Semper)

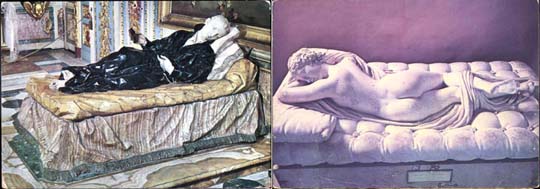

In The Life of Forms in Art, Henri Focillon argues against the antithesis of form and matter. For him, art is bound to matter, and "unless and until it actually exists in matter, form is little better than a vista of the mind, a mere speculation on space that has been reduced to geometrical intelligibility." (p95) According to Focillon, "matter, even in its most minute details, is always structure and activity, that is to say, form." (p.96) and each kind of matter has a certain "formal vocation." But the life which inhabits matter undergoes a metamorphosis as it becomes a substance of art, and technique is a "whole poetry of action" as a means to achieve metamorphoses.

Konrad Fiedler described the achievement of classical Greek architecture as the complete intellectualization of all the material elements of building. "We can speak of understanding a Greek building from the great period only when we perceive how the force that strives for a pure expression of form has taken command of every part of the building." ("Observations on Architecture, in Empathy, Form, and Space, p. 134) Still, Fiedler is careful to note that "Form has no existence except in material, and the material, to the mind, is not only the means by which form expresses itself but the medium in which form achieves existence."

For Heinrich Wölfflin, the force of form (Formkraft ), the opposition between the tendency of matter towards formless collapse and the opposing force of will, life, or whatever, sets the entire organic world in motion and is the principle theme of architecture.

For Ferdinand de Saussure, "language is a form and not a substance." (Cours, p.169)

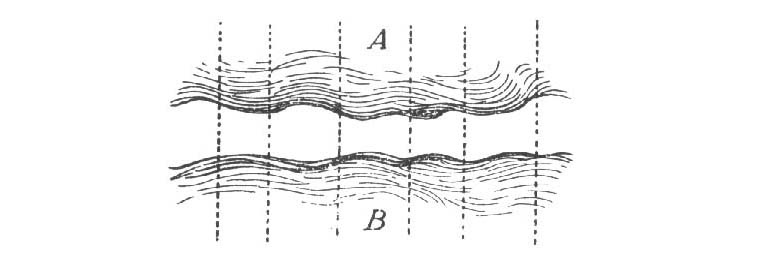

For Deleuze and Guattari, the distinction between matter and form is characteristic of "Royal Science", the science of a society divided into governors and governed. For nomad science the relevant distinction is material-forces rather than matter-form. Materials for nomad science are not homogenous, and form is not fixed. The singularities or haecceities are already like implicit forms that are topological rather than geometrical, and that combine with the processes of deformation: for example the variable undulations and torsions of the fibers guiding the operation of splitting wood. "energetic materiality in movement" (see Thousand Plateaus, p 408)

(see transcendent / immanent) (see also natural form)