Emergence refers to the appearance of patterns of organization and is one of the key concepts of complexity and a-life.It is sometimes referred to as a situation where the whole is greater than the sum of the parts, because it cannot be analyzed by taking the parts apart and examining them separately. One reason for this is that in a complex phenomenon showing emergent properties, the parts become a determining context for each other, and these patterns of feedback contribute to the appearance of the emergent phenomenon. For Michael Polanyi, " Evolution can be understood only as a feat of emergence."

Read Moreorganic

First page of Robert Fludd's Ars Memoriae 1619, showing the "eye of the imagination."

imagination

For Aristotle, in De anima, imagination is the intermediary between perception and thought. The perceptions brought in by the five senses are first treated or worked upon by the faculty of imagination, and it is the images so formed which become the material of the intellectual faculty. (Yates, p 32) Hence "the soul never thinks without a mental picture."

In the eighteenth century, "Fancy" or "imagination" applied to non-mnemonic processions of ideas. When images move in the mind's eye in the same temporal and spatial order as in the original sense-experience, we have "memory" This relation between imagination and memory follows Aristotle as well, for whom memory is a collection of mental images from sense impressions of things past. How do we distinguish between our own memories and our imagination? Modern researchers focus on "source memories" -- where and when we experienced something. Memories are generally accompanied by source memories, while imaginative thoughts do not have the same contextual components in time and space. But the loss of source memories or the imagined sense of location in time and space that can accompany dreams or vivid fantasies can make us unable to distinguish between memory and imagination.

Coleridge distinguished fancy from imagination, paralleling his distinctions between mechanical and organic. His theory of fancy singled out the the basic categories of the associative theory of invention: the elementary particles, or "fixities and definites" derived from sense, which he distinguished from the units of memory only because they move in a new temporal and spatial sequence determined by the law of association, and are subject to choice by a selective faculty -- the judgement of eighteenth-century critics. (Abrams, Mirror and the Lamp, p 168. Coleridge Bigraphia Literaria chapt. 13)

As opposed to this "aggregative" mechanical combinatory, Coleridge developed an organicist theory of the imagination, which is modifying and "coadunating." (a term from contemporary biology meaning to 'grow together as one.') He described the imagination as "vital" as "generating and producing a form of its own," whose rules "are the very powers of growth and production." For Coleridge, the imagination is "that synthetic and magical power, which reveals itself in the balance or reconciliation of opposite or discordant tendencies." This faculty "dissolves, diffuses, dissipates, in order to recreate; or where this process is rendered impossible, yet still at all events it struggles to idealize and unify. It is essentially vital , even as all objects (as objects) are essentially fixed and dead."

Thus the free play of the creative imagination makes up its own rules as it goes along and sets them according to the nature of the subject and the inspiration of the poet. "Imagination is no unskillful architect", for "it in a great measure, by its own force, by means of its associating power, after repeated attempts and transpositions, designs a regular and well-proportioned edifice." (Gerard, Essay on Genius, 1774) The "architectonic" impulse of the theoretical imagination renders phenomena intellectually manageable by presenting them in a "corrected fullness." (Sheldon Wolin).

The products of imagination Coleridge adduces most frequently are instances of the poet's power to animate and humanize nature by fusing his own life and passion with those objects of sense which, as objects, 'are essentially fixed and dead.' (Abrams Mirror and the Lamp, p 292) M. S. Abrams points out that almost all examples of this secondary or 're-creative' imagination would fall under the traditional headings of simile, metaphor, and (in the supreme instances) personnification.

"What distinguishes the worst of architects from the best of bees is this, that the architect raises his structure in imagination before he erects it in reality." Karl Marx, Grundrisse

"Imagination is an act by which we mentally simulate something that previously existed as a vague content of our sensation as sensuous, concrete form. If we then apply the same word to abstract thoughts, we thereby imply that these too are accompanied by mental images. " (Robert Vischer, "On the Optical Sense of Form," 1873) For Robert Vischer, the artist's imagination reunites the senses and the soul. "Both, in fact, were originally one, but in the course of its development the intellect placed itself in opposition to the senses, and only the artist succeeds in achieving their reunion." (p116)

For Kant, the imagination,(Einbildungskraft ) as a productive faculty of cognition, is very powerful in creating another nature, as it were, out of the material that actual nature gives it. Imagination is the faculty of mind which enables us to combine representations. (see Critique of Judgement sect. 49. see also intuition.) Using the etymology of Bild, one can say that the imagination synthesizes the manifold of intuition into a tableau-like unity, and Kant assigns an essential role to the imagination in synthesizing the disparate mental realms of sensibility, understanding, and reason. (See Gasché , p 217) Yet for Kant, the imagination is unequal to the ideas of Reason. The experience of the sublime, either in the form of magnitude or power, causes a painful awareness of the inadequacy of the imagination, but for a rational being there is a pleasure in this awareness, a harmony in this contrast. (see sect. 27) Kant uses the German word das Erhabene, which can mean raised, embossed, or lofty.)

Freud, too, stressed the inadequacies of the imagination, which he described as "the over-accentuation of psychical reality in comparison with material reality." (Das Unheimliche , p.244) In his descriptions of the uncanny (unheimlich ), Freud observed a weakening of the value of signs, in which the symbol ceases to be a symbol and "takes over the full functions of the thing it symbolizes." For Freud, this assertion of "the omnipotence of thought" requires the invalidation of the arbitrariness of signs and the autonomy of reality as well, placing them both under the sway of fantasies expressing infantile desires or fears. (Kristeva, p. 186)

For Gilles Deleuze, imagination is a circuit between the actual and the virtual. Imagination means how we see and how we learn to see, how we suppose the world works, how we suppose that it matters, and what we feel we have at stake in it.

In a very different context, Arjun Appadurai describes the joint effects of media and migration on the work of the imagination as a constitutive feature of modern subjectivity. This is a collective imagination, not the faculty of a gifted individual, and it forms the basis for a "community of sentiment." (what anthropologists call a sodality) Here Appadurai follows Benedict Anderson's analysis of the modern nation as "an imagined political community." For Anderson, "it is imagined because the members of even the smallest nation will never know most of their fellow-members, meet them, or even hear of them, yet in the minds of each lives the image of their communion." (Imagined Communities, p. 6) Appadurai describes media and migration as resources for experiments with self-making in all sorts of societies, for all sorts of persons. The mobile and unforeseeable relationship between mass-mediated events and migratory audiences defines the core of the link between globalization and the modern. In this context, the work of the imagination is neither purely emancipatory nor entirely disciplined, but is a space of contestation in which individuals and groups seek to annex the global into their own practices of the modern. (p.4)

(see also public / private)

For Appadurai, "The imagination is today a staging ground for action, and not only for escape." (an expression which should gratify those whose slogan in 1968 was "l'imagination au pouvoir." ) He describes "culturalism" as a mobilization of identities consciously in the making and as the most general form of the work of the imagination.

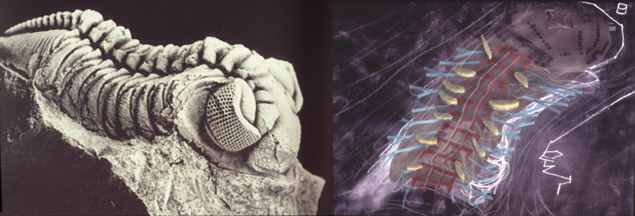

natural form

"Organic forms have a general character which distinguishes them from artificial ones.... We come then to conceive of organic form as something which is produced by the interaction of numerous forces which are balanced against one another in a near-equilibrium that has the character not of a precisely definable pattern but rather of a slightly fluid one, a rhythm...There is, in a human work of sculpture, no actual multitude of internal growth-forces which are balanced so as to issue in a near-equilibrium of a rhythmic character. We should therefore not expect that works of art will often arrive at the same type of form as we commonly find in the structures of living matter. Much more can we anticipate an influence of man's intellectualizing, pattern-making habit of simplification, diluted perhaps by an intrusion of unresolved detail." (Waddington (1951) in L.L. Whyte, ed. Aspects of Form)

Read Moreorganism

"Organism" is derived from the same word as organ: in Latin, organum ; in Greek, organon, which means tool, and was the title given to Aristotle's logical writings to emphasize the idea of logic as a tool helping the other sciences. The instrumental view lies to some degree within the word organism itself: a system of organs, a whole composed of parts, where each part is a functional tool related to the other parts and the whole.

Read Moreplaytime 1

I entitled this lecture "Playtime" long before I had any clear idea what I would talk about, and during the past few months the title has often seemed to have a life of its own, gently prodding me towards levity, cajoling me to stop attaching excessive importance to every thought, to every turn of phrase. But it is not so easy to think playfully, to escape the censorships, the policing of thought which we all-to-easily succumb to and collude with. (Why is it so hard to play?) In this lecture, I have not altogether resisted the academic urge to define play, to fix in place that which should escape definition, to close what should be open. But, I have tried to follow a path opened up by the idea of play, a path both made and found. I might describe it as a kind of autopoetic search for ways of talking about technology and architecture today, in ways mediated by concepts of both play and time. Thinking about play has also afforded me ways of talking about the formation of subjects, about relations between technology and nature, about the 1960's, and about the politics of liberation.

Read Moreplaytime 2

Feminist interpretations of gender symbolism offer an important way of correlating the social self and technology. In societies where the nurture of children is gendered labor, the birth of the psychological self is necessarily defined in relation to a mother-world. (An interpretation fetishized by Linneaus when he devised the term mammals, meaning "of the breasts", to distinguish the class of animals embracing humans, apes, ungulates, sloths, sea-cows, elephants, bats, and all other organisms with hair, three ear-bones, and a four-chambered heart.) The difficult and painful social labor of the infant is marked by the contradictory desire to remain in, or return to, oneness with the mother-world, but also to become a separate person. But that world is different for male and female infants, for the mothering received by boys and girls is different. According to Nancy Chodorow, Jane Flax, and other feminist interpretors of "object theory", mothers tend to experience their daughters as more like and continuous with themselves and to experience a son as a masculine opposite. As a result, the identity of the male child entails a stronger sense of separation and control, of self-definition in relation to persons unlike himself, while the female child continues to experience herself in terms of merging and identification. The male child consequently establishes relatively rigid ego boundaries, while the female's remain more flexible, Masculinity comes to be defined through the achievement of separation, while feminity is defined through the maintenance of attachment. The limitations of Banham's relation to technology may well derive from technology's role as a transitional object in a decidedly masculine project of autonomy and mastery. The solution seems to me to lie less in rejecting technology or radically opposing it to architecture but in recognizing the greater complexity of our relations to gender, nature, and technology. (and learning to play)

Read More