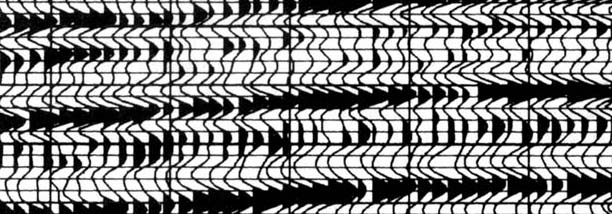

Resonance: when waves resonate, their amplitudes pile up on top of each other, as opposed to interference, which reduces their amplitudes.

A feedback loop creates a resonance that grows without bound.

The Desana Indians of Columbia describe the sky as a brain, its two hemispheres divided by the Milky Way. Their brains, they say, are in resonance with the sky. This integrates them into the world and gives them a sense of their role in the cosmos.

The qualitative aspects of pleasure have been difficult to formulate for psychoanalysis, which uses the "hydraulic" model of tension and release. Hans Loewald suggests that "resonance" between systems of psychic organization, (love, for example) forms of "hypercathexis," might help understand the pleasure in higher organization and unpleasure in less or lower organization -- of the exitation inherent in living substance. (this is similar to Kant's philosophical pleasures -- see critique of judgement )

Ilya Prigogine and Isabelle Stengers talk about the resonance between theological discourse and theoretical and experimental activity in the success of the clock metaphor of the universe. Gilles Deleuze proposes that "philosophy, art, and science come into relations of mutual resonance and exchange, but always for internal reasons." For Deleuze and Guattari, the interaction of actual and virtual is a resonance.

For Deleuze, "the central state is constituted ..by the organization of resonance among centers." (Thousand Plateaus, p.211) "a central computing eye scanning all of the radii."

Rupert Sheldrake believes that morphogenetic events resonate with each other, that it becomes progressively easier for a particular form to occur as its occurrences accumulate. He cites the formation of crystals as an example, in which occurrences of a new cristalline form seem to occur shortly after a first one is observed, in places with no direct relation to the first occurrence. For Sheldrake the probability of the new form occurring increases rapidly with each occurrence, starting with the first.

One wonders, however, why Chinese isn't easier to learn if so many people speak it.